We’ve now covered (covered…I use that word loosely, more like overviewed) the amillennial and premillennial positions, and now we come to a lesser known position that is gaining popularity, namely, postmillennialism.

As a review, this is helpful from an article titled “Postmillennialism” by Barry Cooper at Ligonier:

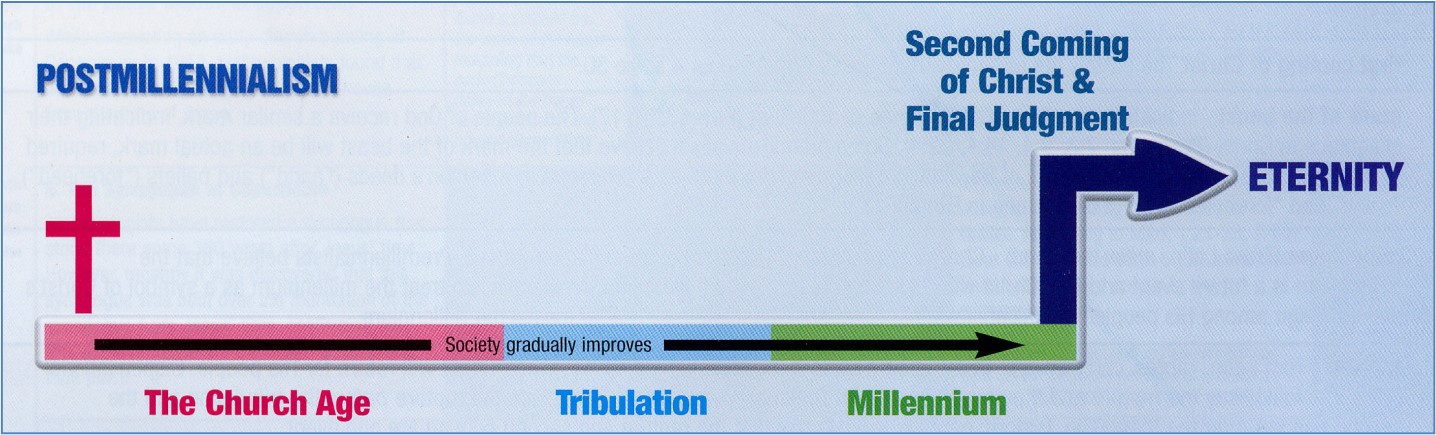

The three positions differ on when Jesus will return. So you’re premillennial if you believe Jesus will return before the millennium. (The millennium is the period of time described in Revelation when Christ will reign with His saints.) You’re amillennial if you don’t believe there will be a literal earthly millennium before Jesus returns. And you’re postmillennial if you think Jesus will return after the millennium, after the world has been successfully evangelized.

He sums up the postmillennial position well when he writes:

Good will gradually triumph over evil. There won’t be a sudden 180, taking the world from overwhelmingly evil to overwhelmingly good, all in the moment of Christ’s return. Instead, across history, the kingdom of God has been growing, and it continues to grow even now, so that there will eventually be a glorious, extended period of time in which the rule of Christ will flourish on the earth. And after that, the Lord will return.

Postmillennialism teaches that the forces of evil will be gradually defeated by the gospel throughout history up until the return of Christ, and because of this, its adherents like to refer to it as an “optimistic” eschatology. In other words, rather than Christ coming back to rescue the church, He will come back to a victorious church. Historically, this view became increasingly popular during times of prosperity within the church – i.e. when the political climate is friendly to Christianity or great awakenings of the church are being witnessed. However, during times of strife (war, etc), this view tends to wane. The earliest postmillennial writer was Joachim of Fiore (AD 1135-1202), and supporters of this view include Jonathan Edwards, R. C. Sproul, B. B. Warfield, Jeff Durbin, and James White.

At its core, postmillennialism teaches that by Christ working in and through believers, the great commission of Matthew 28 will be fulfilled and all the earth will be evangelized before Jesus’ return.

Pray then like this: “Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. 10Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. 11Give us this day our daily bread, 12and forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. 13And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. (Matthew 6:9–13 ESV)

They would also see the Lord’s prayer as an expectant prayer. When they pray “your kingdom come”, they would expect that as Jesus answers that prayer prior to His return, He would be ushering in His kingdom such that when He returns, His kingdom is already established.

Postmillennialism does not require a belief in a literal 1000 year millennium, only that Jesus returns to a world where the gospel has had a real effect. Nor does it require a utopian understanding of perfection prior to the return of Christ, only that the gospel has been preached and because of it, the church has had a positive influence on culture such that society is generally moral. How general is defined varies among postmillennial believers, but they all would believe that Jesus does not suddenly reform culture at His second coming, but is gradually reforming culture until His return.

Postmillennium has a diagram too, and like amillennialism, it is pretty simple.

In recent years, proponents of the postmillennial position have begun to shift on the timing of the millennium in such a way that it overlaps the church age as amillennialism teaches. This shift has caused the discussion to focus more on the nature of the millennium than the timing of the millennium. Because of this, proponents like Keith Mathison have begun to see a variant view within postmillennialism that would differ from the classic postmillennialist. He writes on his blog:

I was introduced to postmillennialism by some of these late twentieth-century postmillennialists. I never believed a “golden age” version of postmillennialism as found in authors such as Boettner. I have argued for decades that the millennium of Revelation 20 is symbolic of the period of time inaugurated by the Son of Man at His First Advent at the point when He came up to the Ancient of Days to receive dominion, glory, and a kingdom – when He received all authority in heaven and on earth. It concludes at His Second Advent. My understanding of the time of the millennium overlaps, therefore, with the understanding of many amillennialists. Some differences remain regarding the nature of the millennium, but on this point I also differ with some of my contemporary postmillennialist friends. I’m not as certain as some of them are about what the gradual growth of the kingdom during the present age will look like “on the ground.” In other words, I’ve never been a theonomic postmillennialist.

He introduces the idea of theonomic postmillennialism as a variant of the classic position. Theonomy comes from the Greek words “theos” (God) and “nomos” (law) and means simply “God’s law”. A theonomic society would be a society that follows God’s law. Note that it does not require the society to actually be a Christian society, merely that it adheres to the law of God. At some level, all Christians want a theonomic society, but we know that as long as humans are in charge, any form of theonomy would be a shadow of the theocracy we will live in when Jesus is our King in eternity. That said, many postmillennial believers do hold to a view of theonomy that would positively say that culture will be conformed to God’s law through the preaching of the gospel and the influence of the church prior to the return of Christ.

That is what Mathison is referring to as theonomic postmillennialism.

So, in a nutshell, that’s postmillennialism. There is much more to say about it, and like all the other views presented in these posts, the focus is on our hope in Jesus and His power to change the world. There are important differences between all of the positions we have seen so far, and while some of the differences are pretty large, good and godly men have held all of them throughout the history of the church.